Airbnb Weibo Campaign

In recent years, Airbnb has grown globally at rates of 300-400%, and the company has forecasted profits of up to US$3.5 billion by 2020. Yet the home-sharing platform faces steep challenges in China, both from external factors and self-made obstacles. Abroad, there are also hurdles to overcome when it comes to attracting the Chinese outbound market, but the rise of millennial travelers and changing attitudes could be the key to future success.

The Chinese sharing economy

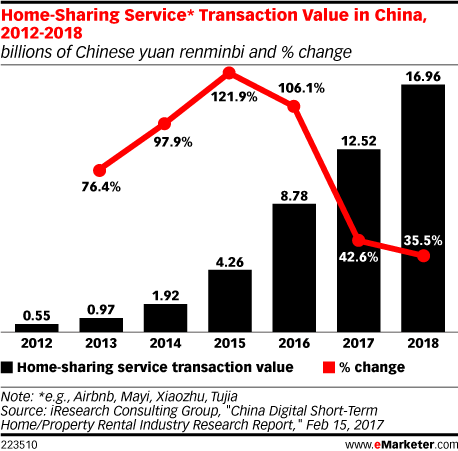

China does have an established sharing economy, especially when it comes to car/ride sharing apps, which have been popular for many years. And according to a February 2017 report, home sharing is close behind in terms of interest and demand. Home sharing in China is predicted to generate RMB12.53 billion in transactions this year, and rising to nearly RMB17 billion in 2018.

However, there are some cultural hurdles to overcome, namely issues of trusting strangers in a country where personal connections are so important. For guests, how can they be sure that an apartment or room will look like the photos? And how can hosts trust a stranger to stay in their home?

Challenges in China

Competitors

Airbnb has strong, local competitors in China, from companies that have already had success in dealing with issues of trust in the home-sharing economy. With 430,000 listings in China and other cities in East and Southeast Asia, as well as backing from both Ctrip and Expedia, Tujia is thriving. It may be known as “China’s Airbnb”, but Tujia’s business is quite different, offering more property management services rather than Airbnb’s peer-to-peer model, which helps alleviate trust issues for both hosts and guests.

Another, smaller competitor is Xiaozhu. This home-sharing company is more similar to Airbnb in its focus on peer-to-peer rentals. It assuages hosts’ concerns by offering training to hosts and security screening of guests.

There’s a history of home field advantage in China when it comes to business – local companies not only have extensive local knowledge and networks, but also receive more government support. For example, after several years in China, Uber gave up in August 2016, and sold off its China services to Chinese company Didi Chuxing. Other successful foreign companies, such as Amazon or Facebook, have also failed to take the place of local equivalents.

Tujia’s website promotions

Self-made challenges

Airbnb has worked to create a China-specific strategy, with a Chinese rebrand in March 2017. While outside of China, users log in to Airbnb via Facebook, users in China, where Facebook is blocked by the ‘Great Firewall’ can log in via popular Chinese social media platforms WeChat or Weibo instead. Airbnb offers Mandarin-language support, allows payment via the popular Alipay, and uses Sesame Credit, a Chinese social credit scoring system, to help screen and validate users. However, while the service allows WeChat login, it does not allow for payments via WeChat – one of the most popular forms of online payment in China today.

Airbnb’s Chinese site is more focused on overseas trips than local recommendations, and there are some usability issues. Ms. Wang Tianyi, an Airbnb user from Jiangsu Province who lives in Beijing, explains that she prefers to use Airbnb’s English platform to get the English-language version of addresses and reviews. Sarah Zhang, from Guangzhou, says that part of the reason she doesn’t book apartments through Airbnb is that she finds the website difficult to use compared to sites she’s more familiar with, like Booking.com.

Then there’s the issue of Airbnb’s Chinese name, Aibiying (爱彼迎), introduced this March. Adopting a Chinese name should be part of a Chinese marketing strategy, and the name’s intended meaning, “to welcome each other with love”, is positive. However, in this case, the Chinese name may have done more harm than good. Not only is it awkward to say for Chinese speakers, but the way it sounds also has sordid connotations. “Their name is a joke. It’s like an angry Chinese employee gave them this name,” says Sarah Zhang. “Airbnb’s Chinese name is quite terrible,” Wang Tianyi agrees. “I do not like it, but because I was already familiar with the brand, I didn’t wonder too much about the name. But for first time users, I do think the name … can put off some people.”

Airbnb Chinese name unveiled

The picture abroad

With 142 percent growth in outbound travel from China in 2016, and with much less competition, the picture outside of China is potentially much rosier for Airbnb. But even here, there are challenges.

A reluctant market

“My friends who have studied abroad or traveled abroad are most likely to know about the platform. For all other people, it is hard to convince them to stay at an Airbnb,” says Wang Tianyi, who has used the service since a friend recommended it to her in 2014, when she was studying in the UK. Even for experienced overseas travelers with Western outlooks, the brand can be a hard sell. Sarah Zhang has traveled extensively and previously worked for the British Consulate in Guangzhou. She started renting apartments overseas in 2011, after traveling together with friends this way in Europe. She says she prefers the privacy and space of renting an apartment rather than staying in hotels, but she uses Booking.com rather than Airbnb, as that’s what she’s used to.

The concept of apartment sharing isn’t taking off with China’s rich, either. According to the Hurun Report’s 2017 study on luxury Chinese travelers, only 25% have even considered Airbnb-style accommodation, versus 48% for boutique hotels and 45% expressing interest in yacht cruises. 69% of respondents reported unfavorable or lukewarm attitudes to staying in Airbnb-style accommodation in the future, preferring hotels instead.

Millennial opportunities

Where there is room for growth, though, is among younger Chinese travelers. According to Airbnb’s 2016 millennial report, 83% of Chinese Airbnb users come from this generation, the highest percentage globally. Furthermore, the number of millennial Airbnb travelers in China has more than quadrupled year on year. And in more good news for Airbnb, millennials make up at least 35% and even up to two-thirds of all Chinese outbound travelers.

Airbnb’s survey of millennials showed that Chinese cared more than their UK and US counterparts about having unique experiences and living like a local while traveling to truly understand a place. These are the kind of advantages that Wang Tianyi sees about Airbnb, and she’s used the service in Blackpool, London, Paris, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Edinburgh, Bologna, Porto, Lampedusa, New York, Boston, Palermo, Malta and Beijing. “It’s different from hotels. I like the different styles – every house has its own, and it’s different in the UK from France etc. It’s more interesting. Sometimes it’s even more expensive than staying at hotels, but I chose to stay at Airbnb anyways,” she says.

Unlike Sarah Zhang, who prefers apartment accommodation for total privacy, Wang Tianyi also enjoys staying in private rooms through Airbnb, with local hosts. “They give me tips on what to do or where to eat. In Bologna, the host told me about a specialty shop for chocolate. And sometimes when winding down from the day out, I enjoy having a drink with the host. This is a good way to learn more about the local culture. When I stayed in Blackpool, the host drove us to the park we wanted to go to, because it was quite far. In Edinburgh the host was a good cook and baked for us every morning for breakfast.”

With the importance of word of mouth for marketing in China and in getting travelers to first try Airbnb-style accommodation, stories and experiences like these can have a big impact. California-based Chinese blogger Chenyu Zheng has over 300K online followers in China and recently completed an entire year of living exclusively in Airbnbs. She blogged about her experiences, as well as recording them on Instagram, and her book, 365 Days On Airbnb, is due to be published by China’s CITIC Press, later this year.

Whether it’s at home or abroad, attracting the Chinese market isn’t all smooth sailing for Airbnb. But the real challenge may simply lie in changing attitudes, and here, the presence of competitors in the domestic market could be blessing in disguise, familiarizing Chinese with the concept of apartment sharing before they head abroad. Overseas, the rise of millennial travelers and the rapidly evolving nature of Chinese tourism could also give Airbnb the boost it’s looking for.

Chenyu Zheng’s Airbnb stay

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito para mantenerse al tanto de las últimas noticias

NO COMPARTIMOS SU INFORMACIÓN CON TERCEROS. CONSULTE NUESTRA POLÍTICA DE PRIVACIDAD.

This website or its third party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and required to achieve the purposes illustrated in the cookie policy. If you want to know more or withdraw your consent to all or some of the cookies, please refer to the cookie policy. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to browse otherwise, you agree to the use of cookies.